Controversial pitching ace Trevor Bauer signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers last week, which was remarkable on a number of levels:

- Bauer only secured a three-year deal, whereas most 30-year olds coming off a career year might be inclined to try to broker a deal for much longer.

- Bauer had talked about wanting to pitch every 4th day instead of every 5. With a rotation that also consists of Clayton Kershaw, Walker Bueller, David Price and promising young pitchers in Jose Urias, Dustin May and Tony Gonsolin, it's hard to imagine the Dodgers skipping one or more of them to give Bauer an extra turn, or otherwise messing with their schedules to satisfy him. Kerhsaw in particular is supposedly a creature of routine, and presumably has the clout needed to thwart any such plans.

- There had also been talk of Bauer wanting to garner distinction as the highest paid player in the game at least for this year, and possibly next. This deal doesn't quite get him there, but Year 2 could really be a doozy in that regard.

- He gets a $10 million signing bonus. In the first year of the deal he's earning $28 million, and the second will earn him $32 million. However, his employ for 2022 remains to be seen because...

- ...he has opt-out clauses after each year.

There are also caveats about the team deferring his 2021 salary if he opts out after this year, and the buyouts he'd receive if opting out ($2M for 2021, $15M after 2022), so he could effectively earn $85 million for two years' work, or $102M if he sticks around for all three.

Assuming he does well and enjoys himself in 2021, it's hard to imagine him turning down a guaranteed additional $47 million for one more year's work, but I guess you never know. I suppose if he's lousy in 2021 he's got even more reason to stay.

Bauer evidently does not care for long term commitments, stating that he prefers "flexibility" and not being despised by the fanbase when he's still earning huge piles of money even as his skills erode and he turns into a pitching machine in his late 30s. I'm paraphrasing here.

Of course, if he's lousy as soon as 2021 or 2022, he'll be plenty despised anyway.

Was He really That Good???

And make no mistake: There is a chance that he will in fact be lousy in 2021. Or at least that he'll be mediocre. That may sound like an odd claim when discussing the reigning NL Cy Young Award winner, but stick with me here:

Bauer won the 2020 NL CYA by going 5-4 with an NL-leading 1.73 ERA. He had 100 K's against only 17 walks in 73 innings pitched. He led the Senior Circuit in WHIP, Hits/9IP, adjusted ERA (5th best all-time and 3rd best since the Dead Ball Era), shutouts and complete games (2 each).

If you clicked on the ERA+ link above, then you may have noticed another name on that list: Shane Beiber, former teammate of Bauer's in Cleveland, who won the AL CYA in 2020 and whose adjusted ERA of 281 is 2nd since the Dead Ball Era, behind only Pedro Martinez' amazing Y2K campaign.

In fact, if you look at that list again, you'll see something very curious: Among the top 21 names/seasons on the list, four of them are from 2020. Most are all-time greats, though there are a few anomalies, specifically:

- Tim Keefe in 1880, who holds the top spot despite appearing in only 12 of his team's 83 games and pitching only 105 innings, and

- Dutch Leonard, a decent pitcher who seems to have taken full advantage of the fact that a whole bunch of AL hitting talent went to the Federal League in 1914.

Keefe would eventually be elected to the Hall of Fame, even if he was just getting started in 1880. The other names are almost exclusively upper-echelon Hall of Famers: Greg Maddux, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson and Pedro Martinez each appear twice in the top 20, as does Roger Clemens. Hall of Famers Bob Gibson, Pete Alexander, Three-Finger Brown and Keefe each show up once. Other seasons are ones for the ages, if not by eventual Cooperstown cronies: Doc Gooden in 1985 and Zach Greinke in 2015.

But then there are the four 2020 seasons, Bauer, Beiber, Dallas Keuchel and Yu Darvish. Darvish and Keuchel are both fine pitchers - Keuchel won the CYA a few years ago and Darvish is actually the all-time career leader in K/9, in case you didn't know (I didn't) - but neither of them is going to get a plaque in Cooperstown someday.

For that matter, if you look at the top 50 seasons all time in ERA+, there are five(!) of them from 2020, since Dinelson Lamet also makes the cut, tied at #39 with Greinke's Cy Young year of 2009. Only four other seasons appear twice on that list, and only one before 2020 appeared three times: That was 1997, when Pedro, The Big Unit and the Rocket all had incredible seasons at the same time. And we have our suspicions about how the 34-year old Clemens pulled that off...

Seems odd, right? We've got stats going back to 1876 - 146 years! - and 5 of the top 50 pitcher-seasons all come from this year? Are we in some kind of pitching renaissance?? Will we all one day tell our grandchildren how we once saw the great Dinelson Lamet pitch the same year as Trevor Bauer and Dallas Keuchel???? (Well, we didn't really see them, nobody did, since we were all stuck at home all year, but you know...)

Of course not.

Welcome to Small Sample Size Theatre!

These are all, or at least some of them must necessarily be, a mirage of the shortened season. Just like Keefe's truncated 1880 campaign, which has topped the list ever since there was a list of single-"season" adjusted ERA leaders, many of these appearances are here only because they were not forced to pitch a full season. Nobody started more than 13 games in 2020. Bauer started only 11. It was basically a third of a season, maybe a smidge more. As good as they are, it can be all but assured that, had they another ~20 starts to make in 2020, Some of those five pitchers would no longer have been on that list of the top 50 ERA+ seasons in MLB history. Lamet was an unaccomplished prospect working his way back from season-ending surgery. Keuchel had pitched to a cumulative 3.77 ERA in four years since he won the CYA. They certainly would have fallen back to the pack if given the chance.

Might Trevor Bauer have done so too??

Coming into 2020 Bauer had, shall we say, a checkered past. Entering the 2018 season he had a fairly pedestrian 4.36 ERA, equating to a 99 ERA+, in 728 innings across six MLB seasons, including the previous four as a rotation stalwart for Cleveland. It was a pretty good sample size, indicating that Bauer was a LAIM, but not much more.

Then in 2018, he seemed to have turned a corner. He was among the league leaders in Wins, ERA, strikeouts and a bunch of other stats when he got hit by a comebacker off Jose Abreu's bat in mid August and missed a month and change with a stress fracture in his leg. Upon his return he pitched only 9.1 innings across three games, as the team didn't want to risk reinjuring him since they had basically wrapped up their division in mid-August. Bauer pitched in relief in three postseason games, giving up three earned runs in four innings, including taking the Loss in the deciding Game 3 of the ALCS against Houston. (That was a Cleveland home game, so presumably Houston did not get any help from the rubbish receptacles.)

His 2019 season was more up and down. He pitched very well in April (5-2, 2.45 ERA) then in May, hmmm, not so much (1-5, 5.50, and also 7 unearned runs) . He was back to form in June (4-1, 3.06 ERA), was doing OK in July, and despite a few clunkers among his usual quality starts in those two months, was having a decent year. Coming into his last start in July, he had a 9-7 record and a 3.49 ERA, with 179 K's in 152 innings, including 15 Quality Starts in 23 outings. Pretty solid numbers, if not the type that win any awards.

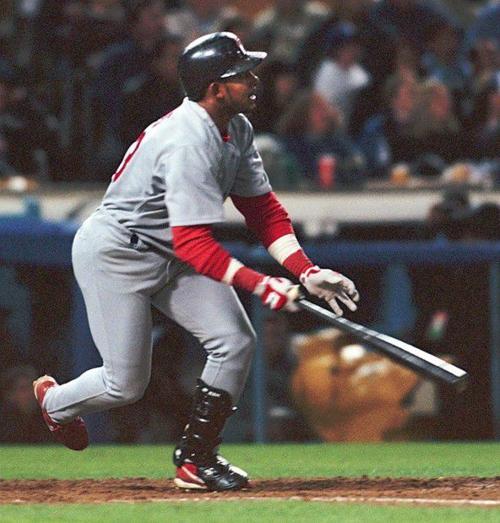

But then, this happened:

And that bit of long-toss over the centerfield fence, as you may know, was the last pitch he would ever throw for Cleveland. This outburst, not to mention all the times he'd gotten into trouble on social media, and for berating fans who criticized him, gave Cleveland all the excuse it needed to rid itself of him. The Tribe suspended and then promptly traded him to the Reds (with the Padres) for Franmil Reyes and Yasiel Puig, among others.

Bauer had a few decent starts for Cincinnati down the stretch in 2019, but overall pitched to an ERA of 6.39 in a Reds uniform that year. They skipped his last start of the season against the lowly Pirates, who finished with 93 Losses and the 11th worst average runs scored per game.

2020 Hindsight:

Amazingly, in 2020 Bauer came back and pitched remarkably well, albeit in about a third of a full season. You would have to assume the law of averages might have brought his ERA back up closer to his career mark in the ~4 range if he'd had the rest of the season to pitch, though it presumably still would have been a good year.

Additionally, for the pitching he did accomplish, consider his competition. Remember, in 2020 there really was no "National League" and "American League", not until we got to the playoffs. The Reds played in the "Central Division" consisting of only the 10 AL & NL Central teams, and 9 of those 10 teams were among the dozen worst offenses in MLB by average Runs Scored/Game, the lone exception being the White Sox (5th best).

Among those 11 starts, Bauer had:

- Two against the Cubs, who despite winning the NL Central, had the 11th lowest runs scored average in MLB. He was 1-1 with 3 runs allowed in 13 innings against Chicago.

- Two vs. the Tigers, the 8th worst offense in MLB. He allowed one run in 13.1 innings and fanned 20.

- Three vs. the Brewers, the 4th worst offense in MLB. He was 2-1 with six runs allowed in 20.1 innings and 32 strikeouts.

- One start against the Royals, the 5th worst offense in MLB (7 shutout innings, 9 K's, no balls thrown over the CF fence), and...

- Two starts against the Pirates who had the worst offense in MLB. He allowed two earned runs in 12.2 innings with 19K's, though he lost one of those starts due to three unearned runs.

Alas, he did not get a chance to face his former team in Cleveland, who had the 6th worst run production in MLB last year. The only start he had in the regular season against a team that could actually hit was against the White Sox in September. He gave up two runs in seven innings and struck out five, but took the loss because the Reds had the third worst offense* in baseball last year by Runs/Game, and they scored no runs at all against the Pale Hose pitchers, including Keuchel.

* In terms of batting average, the 2020 Reds were one of the worst hitting teams in MLB history. The team's collective .212 batting average was the lowest for a "full season" by a team since the Dead Ball Era. And it gets worse, believe it or not: Because the The Great American Ballpark is a pretty good hitter's park, their overall offense was actually helped by it! They hit just .204 on the road with a .360 slugging percentage. They're like a whole team of Mike Zuninos.

The only teams who even come close to that hitting ineptitude since 1910 are generally expansion/relocation franchises or historical anomalies:

- In 1963, both the Mets and Colt 45's, recent expansion franchises, hit .220 or worse.

- The 1972 Texas Rangers, in their first year as the transplanted Washington Senators (Part II!) collectively hit .217 and had one player with double digit homers: Ted Ford with 14. The entire AL hit .239 that year and the league owners voted to implement the DH for 1973. Ted Williams retired permanently from managing.

- The 1968 Yankees hit just .214 in the Year of the Pitcher, though they were 5th in the AL in homers so the offense wasn't really as awful as the batting average would suggest. Mickey Mantle hit .237 that year and then retired. That roster also contained several players who would eventually find more success as a manager and/or GM than they ever did as a player, specifically Mike Ferarro, Bobby Cox, Dick Howser, Gene Michael, and the father of Ruben Amaro, Jr., but sadly none of them hit a lick that year.

- And...ummm...I feel like I'm forgetting somethi...

- ...Oh! And also the 2020 Rangers, Cubs and Pirates, all of whom hit .220 or worse.

Again, Small Sample Size Theatre! 31 teams in all of MLB history have hit .220 or worse for the season - only 11 since the dawn of the 20th century - and four of them were this past year! So did Bauer and the others pitch so well because their competition couldn't hit? Or was their competition simply overmatched by the incredible talent of Bauer et. al? Chicken or egg...egg or chicken? I suspect we won't know until we get to see another full season of baseball this year.

Anyway, despite their historically anemic offense, by a quirk of the COVID schedule, the Reds managed to make the postseason. Bauer pitched well in the NLDS, allowing only 2 hits and no runs in 7 innings and change, with 12 K's. Unfortunately, the Reds lost 1-0 to the Braves in the 13th inning, and then got shut out again the next day, 5-0, becoming the only team in history not to score any runs at all in a postseason series.

So there are technically two data points from 2020 suggesting that Bauer can succeed against stiffer competition.

Moreover, before he got hurt in 2018, he had stretches of real brilliance. His last 11 starts before the Abreu comebacker consisted of a 7-1 record and 93 K's in 72 innings with a 1.62 ERA, numbers very similar to those he put up in 2020, and not very different from the rest of his 2018 season to that point. He pitched well that year against the Yankees, Astros, Twins, Rangers, Cubs and A's, all teams that could hit, in addition to beating up on the likes of the Royals and Tigers.

Deeper Down The Numbers Rabbit-Hole...

Bauer's Statcast and batted ball data for 2020 show some interesting things. He had the lowest line drive percentage of his career (17.8%, compared to 22% for his career) as well as the lowest pull percentage (35.4%, compared to 41.2% for his career). He also had the highest launch angle (20.9 degrees, well above his 13.4 degree career average) and the lowest ground ball percentage of his career, 0.72, way below his career mark of 1.12, which is odd, as you would think allowing a higher percentage of fly balls would have allowed more runs, not fewer, especially in that ballpark. His home run rate was right in line with his career marks.

He had the highest strikeout rate and lowest walk rate of his career, which makes some sense when you consider that he spent most of his time pitching against teams who couldn't hit. But more to the point of explaining how all those fly balls and line drives did not turn into runs, his batting average on balls in play (i.e. when he didn't allow a walk, homer or get a K) was a paltry .215, way below both his own career average of .294 and the MLB average of .292.

That .215 BABiP also happened to be the second best in the majors, behind only fellow "Central Division" opportunist Kenta Maeda, who clocked in at a .208 BABiP. Any guesses who Maeda faced the most? That's right: 3x each against Detroit and Cleveland, 2x against Milwaukee and once against Pittsburgh. He also faced the White Sox twice, allowing 2 earned runs in 5 innings each time. He finished 2nd in the AL Cy Young voting.

With Beiber, Bauer, Darvish and Maeda, the #1 and #2 spots in both the AL and NL Cy Young voting all pitched against the same (apparently) impotent competition. Both Beiber and Darvish had only two of their 12 starts against a team that was not in the bottom ~1/3 of the majors in run scoring, the White Sox, of course. Darvish allowed only one run in 14 innings, while Beiber allowed 4 runs in 11 total frames, getting a no-decision each time.

All Ahead Full-Impulse Bauer!

Dodger Stadium is still a pretty forgiving pitcher's park, so it could mask any failings on Bauer's part, at least as regards his pitching. But if he gets lit up on the road a few times (recall the hitter's parks he'll frequent in Arizona, Colorado, Texas and Houston) will we see the old Bauer's temper tantrums again? Will the fans hold back their ire in 2022 for a man making $47 million a year if he starts serving up longballs? Will he blow up at someone on Twitter again, alienate teammates or journalists, or otherwise make himself less than welcome during his tenure?

Probably. But if he can keep pitching like he did in 2020, nobody in Dodger Town will mind all that much. And if not, at worst he'll be gone before Joe Biden's term in office is over. Seems like a pretty good deal for both sides.